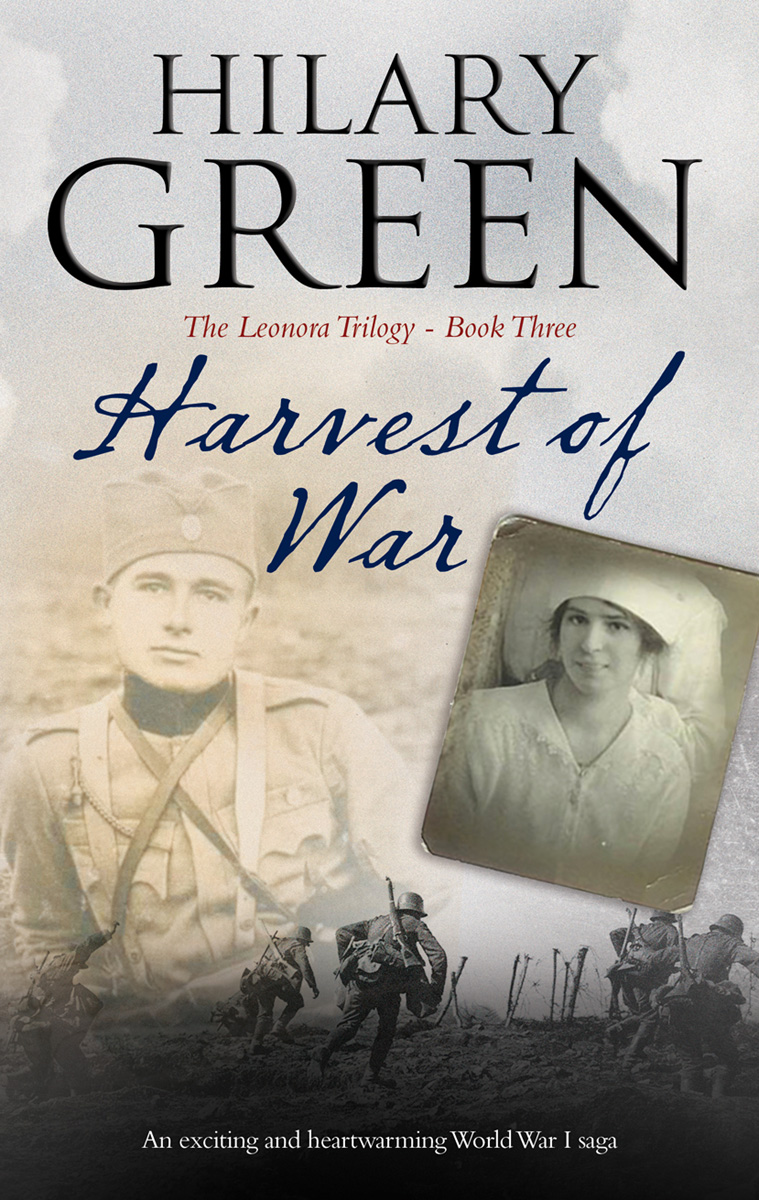

HARVEST OF WAR

The year is 1916. Following their desperate retreat through the Albanian mountains (See Book 2 Passions of War) the remnants of the Serbian army are hoed up in the Greek city of Salonika, their homeland occupied by Austria and Bulgaria. Working as a volunteer for the Red Cross feisty young Englishwoman, Leonora Malham Brown, has secretly become the lover of the dashing Colonel Sasha Malkovic, who has pledged to ask for a divorce once the war is over, so he can be free to marry her. Meanwhile, Leo's fiance, Tom, is engulfed in the horrors of the Somme, where he discovers a shocking secret about her brother Ralph. And Leo herself is keeping a secret from Sasha. When Sasha discovers the truth he and Leo argue bitterly before he rejoins his troops on the battlefield. before the lovers can be reconciled Leo receives terrible news. Tragedy and heartbreak will follow before she finally has a chance of happiness.

Bitola was under constant bombardment from Bulgarian artillery

and from German planes. By Christmas there was scarcely a building in the

city undamaged and even the hospital had been hit. With snow blocking the

mountain passes it was impossible for supplies to get through from the south

and rations began to run short. Working twelve hour shifts on inadequate food,

Leo’s health began to suffer. Looking at herself in the mirror, on the

rare occasions when she had time, she saw a haggard face with hollow cheeks,

and stick-like arms and legs protruding from her swollen belly. She began

to dread her encounter with Sasha more than ever.

Christmas passed, both the western one and the orthodox. Then one evening

she was folding sheets in the tiny storeroom when she heard his voice behind

her.

‘Leo! Here you are! I’ve been searching for you.’

She put down the sheet she was holding and turned slowly to face him. For

a split second she saw the happy anticipation on his face; then it faded to

consternation and finally to anger.

‘My God! What are you doing here in that condition?’

Leo took a deep breath. She longed to throw herself into his arms but the

expression on his face froze her to the spot. ‘My job,’ she replied

quietly. ‘Like you.’

‘Like me? The difference is, I am not carrying a child!’ They gazed

at each other in silence for a few seconds. Then he went on, ‘How long

have you known?’

‘Since … since just after you left Salonika.’ It was only a

small lie.

‘And the child is due, when?’

‘I’m not sure. A month, six weeks …’

He made a gesture of incomprehension. ‘What were you thinking of? How

could you risk yourself, and the baby?’

‘I wanted to be near you.’ Her voice was shaking. ‘And I thought

the campaign would be over much sooner … before the worst of the winter.

I thought by now we would either be in Belgrade, or back in Salonika.’

He shook his head in disbelief. Then, at last, he came close to her and put

his hands on her shoulders. ‘You must go back.’

‘I can’t. Not until the spring comes. All the roads are closed.

But I am in the right place, you see. This is a hospital, and Dr Pierre is

very competent … if he should be needed.’

‘A hospital in a town that is being shelled every day! In a town that

is running out of food! How could you be so stupid?’

Tears scalded her eyes. She moved to him and laid her head against his shoulder.

‘Don’t be angry, Sasha. I want you to be glad, for both of us. We

are going to have a child… our child.’

‘A child born out of wedlock,’ he said. He did not draw back, but

neither did he fold her in the embrace she craved.

She looked up at him. ‘What does that matter? We are going to be married,

one day.’

‘One day. But that could be months, even years away. And the child is

due long before that.’

‘Why should we care? It doesn’t matter to us.’

‘But it will to other people. Even when we are married, to some people

it will still be a bastard.’

The word struck her like a blow in the face. She drew back and stared at him.

He sighed deeply.

‘I am responsible. This is my fault. I must take my share of the blame.

‘

‘Don’t look like that,’ she begged. ‘We should be rejoicing.’

He gazed at her bleakly. ‘You have been completely irresponsible. You

are risking your life, and the child’s. I am afraid I can see very little

to rejoice about. I’m sorry, I cannot …cannot …’ He faltered,

then turned about and left the room.

She called after him but he did not respond. She would have followed him,

but her legs gave way under her and she sank down onto the pile of sheets

and wept.

All the rest of the day she waited, expecting to hear his voice or his footsteps,

convinced that when he had time to think he would come back and apologise

and comfort her. But he did not come; and the next morning she learned that

he had left at dawn to rejoin his troops.